What Made Leigh Bowery So Legendary?

This month, ThePack pays tribute to a man whose all-too-brief life continues to influence the way we think about gender, performance, drag and the art of dressing up for a night out. Leigh Bowery influenced everyone from Lady Gaga to Grayson Perry, Alexander McQueen to Lucien Freud. So, what made him a legend? Allow this Time Out London piece, published in appreciation of Leigh shortly after his death on New Year’s Eve 1994, bring you up to speed…

Picture this. A man is propped against the bar at a London nightspot, suffering the effects of one too many party pills. Looking around, his eyes focus on a colourful being (probably male, though he can’t be sure) parading towards him. Our hapless party animal turns to the nearest friendly face, waves in the general direction of the apparition and pleads: ‘Tell me you can see that too!’ Leigh Bowery had that effect on people.

Born in 1961 and raised in the Melbourne suburb of Sunshine, Bowery moved to London in 1980, drawn by tantalizing images of the post-punk club scene. He arrived as the New Romantics were taking up residence at venues like the Blitz. One of his first gigs was working on the video for Bowie’s ‘Ashes to Ashes’. It wasn’t long before he left his own heroes in the shade.

Bowery’s passion for provocation took many forms. In the early ’80s, he designed and sold clothes (which he later described as ‘Vivienne Westwood rip-offs’) in Kensington Market. But it was his own, unique, extreme style that set him apart. Designer Rifat Ozbek remembers first seeing Bowery at Heaven at the time: ‘You’d think this is it, this is the ultimate, you can’t go further than this, and then you’d see him the next night with a whole new look. He always outdid himself.’

It was as a club creature that Bowery really came into his own. In 1985, he jointly launched a night called Taboo, held every Thursday in a mirror-ball kitsch dive on Leicester Square. Taboo was a nightlife miracle that was uninhibited to the point of being unhinged. On the frequent occasions when the record finished and the needle was left to bounce around the record mat, it wasn’t a cause for embarrassment but for celebration. The fashion freak regulars whooped like dervishes or collapsed in screaming heaps while Bowery, always at the centre of the mayhem, grabbed some hapless person and twirled them around on his shoulders until somebody finally put another record on.

‘I was never interested in simply being a drag queen’

Everyone there who wasn’t George Michael claimed to be a designer, a photographer or a Japanese television personality. At least half the club appeared to be off their collective faces on ecstasy, which partly explains the bizarre sex scenes in the toilets. The club’s door policy was legendary too. The story of doorman Mark Golding holding up a hand mirror to a hapless person in the massive queue and asking ‘Would you let yourself in?’ wasn’t apocryphal, it was pure Taboo.

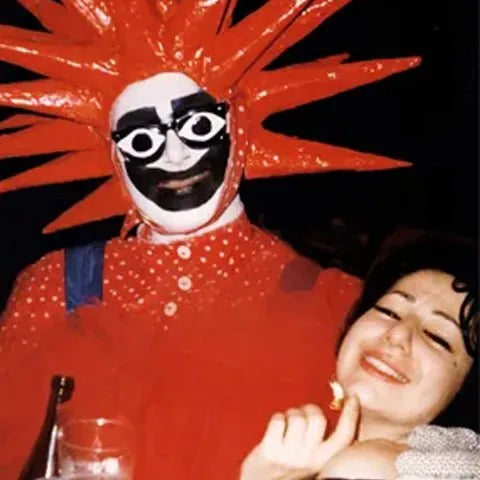

Like all the best clubs, Taboo died in its prime (in 1986) and its loss led to a stream of imitators. By now, Bowery had become an icon of outrage at a time when all else was drifting into sterile yuppie conformity. A natural show-off, Bowery turned exhibitionism into an artform. ‘I was never interested in simply being a drag queen,’ he once said. Using wigs, masks, heavy make-up and clothes he designed and made himself, Bowery transformed himself with each new look. He was prepared to totter around on foot-high platforms or make a fearsome uplift bra out of gaffer tape to give himself a plunging cleavage. One month he was a Wildean aesthete with enormous lashes and wax dribbling down his bald pate, the next, a grotesque clown with crash helmet, painted eyes and a comic-book grin. ‘If people are laughing at me, that’s fine,’ he said. ‘I invented the joke.’

In 1988, Bowery was invited to take his peculiar brand of performance art to the Anthony D’Offay Gallery, where for two weeks he preened, posed and slept behind a two-way mirror. One of the spectators was artist Lucien Freud, who went on to select Bowery as a model, committing his naked body to a stunning series of huge portraits, which rank among his most ambitious work. The exhibitionist was now officially an exhibit.

Leigh Bowery © Lucien Freud

Leigh Bowery © Lucien Freud

As time went on, Leigh’s urge to explore extreme physical states became more pronounced than ever. In a sense, his own death from meningitis was entirely unexpected. Diagnosed HIV positive in 1988 he kept his status from almost everyone including his closest friends. According to Sue Tilley, one of his long-term associates, Bowery wanted to be known as a person with ideas, rather than a person with Aids.

‘If people are laughing at me, that's fine. I invented the joke’

Yet in retrospect, it is tempting to trace the influence of the virus on his body of work, if not his own body. Even as Bowery’s stage persona became less and less recognisably human, drawing on a variety of grotesque masks and rubber, all-over body suits, so his performances became more and more obsessed with bodily fluids.

On one memorable occasion, he gave himself an enema on stage, spraying the contents of his bowels over an astonished – not to mention outraged – audience which included Jean-Paul Gaultier. His last public performance, at the Freedom Theatre in December 1994, involved generous amounts of blood, piss, shit and vomit. As he said himself, he loved to cause a stink whenever possible.

Controversial to the end, Bowery believed passionately that it was ‘in the homosexual nature to be subversive’. When Time Out last interviewed him in December 1994, we asked him whether he saw any irony in the fact that while his performances usually revolved around ideas about sex and sexuality, his own stage persona was curiously sexless. ‘Not at all,’ he replied, shocked at the suggestion. ‘The way I look is very sexy. It’s just that you lot haven’t caught up yet.’

Leigh Bowery ©

This article is sourced from: timeout.com/london. This transformative remix work constitutes a fair-use of any copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US copyright law. “What made Leigh Bowery so legendary?” by Dave Swindells and Paul Burston is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 License – permitting non-commercial sharing with attribution.